Select pages - there are more than 4 available

Angel of the North.

The Angel of the North is a contemporary sculpture by Antony Gormley, located in Gateshead, Tyne and Wear, England. Completed in 1998, it is believed to be the largest sculpture of an angel in the world.

Angles of the North.

The Angles (Old English: Ængle, Engle; Latin: Angli) were one of the main Germanic peoples who lived in Great Britain. They founded several kingdoms of the Heptarchy in Anglo-Saxon England, and their name is the root of the name England ("land of Ængle"). Angles are related to the historical regions of Schleswig and Holstein, today part of southern Denmark and northern Germany (Schleswig-Holstein).

The Angles of the North.

Bernaccia (Bryneich / Berneich).

Situated around modern Durham and Northumberland, the kingdom was based on one called Bernaccia which seems to have been founded during the break-up of (the alleged) Romano-British administration in fifth century Britain. A group of Angles took it over, in AD 547 according to tradition (speculation!), and pronounced the existing name as Bernicia.

The Bernaccian Britons were the descendants of the southern Votadini tribes. The state is mentioned in Old Welsh poetry, in the writings of Nennius, and elsewhere under the name of Bryneich or Brynaich. It is not quite clear whether this is simply supposed to represent a Welsh version of the later Anglian Bernicia, or was the name of a preceding Brythonic kingdom. However, as the name seems to derive from the Brythonic word Berniccā / 'berna', perhaps meaning 'gap' or 'land of mountain passes', the latter hypothesis would appear to be correct. It is possible that the name had its earliest origins in the Brigantes, although this is generally discounted.

Calling upon either Corstopitum, just south of Hadrian's Wall, or Cataractonium (later Catreath of the Mabinogion, modern Catterick) as its capital, Bernaccia encompassed the land to the east of the Pennines, from the northern border of Ebrauc to the mass of the Lammermuir Hills which separated it from the northern Guotodin. Its traditional northern border stretched between Gefron (Yeavering, bordering the Cheviot Hills) across to the sea to the Din Guardi of Nennius. This fortress, Din Guardi or Dynguayth, is equated with Bamburgh thanks to an entry in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and also serves as the probable site of the Arthurian Joyous Gard. It lies midway between the two Roman walls but, considering the fact that the kings of Bernaccia were claimed as descendants of High King Coel Hen, who was also known as the 'King of Northern Britain', it seems likely that the remaining few miles of territory would also be claimed by them. Ynys Metcaut / Innis Metcaud (Isle of Winds) was the Celtic name for Lindisfarne.

According to Gesta Danorum, Dan and Angul (Angel), were sons of one Humbli, who were made rulers by the consent of the people because of their bravery. Dan gave names to Danes and Angel gave names to Angles.

Gesta Danorum ("Deeds of the Danes") is a patriotic work of Danish history, by the 12th-century author Saxo Grammaticus ("Saxo the Literate", literally "the Grammarian"). It is the most ambitious literary undertaking of medieval Denmark and is an essential source for the nation's early history. It is also one of the oldest known written documents about the history of Estonia and Latvia.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gesta_Danorum

Source: https://www.historyfiles.co.uk/KingListsBritain/BritainBernaccia.htm

Lindisfarne.

Lindisfarne, also called Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland. It has a recorded history from the 6th century AD; it was an important centre of Celtic Christianity under Saints Aidan of Lindisfarne, Cuthbert, Eadfrith of Lindisfarne and Eadberht of Lindisfarne. After the Viking invasions and the Norman conquest of England, a priory was re-established. A small castle was built on the island in 1550.

There's something fishy about Lindisfarne (Holy Island).

The name Lindisfarne has an uncertain origin.

Ynys Metcaut / Innis Metcaud (Isle of Winds) was the Celtic name for Lindisfarne.

Both the Parker and Peterborough versions of the Anglo - Saxon Chronicle for 793 record the Old English name Lindisfarena.

In the 9th century Historia Brittonum the island appears under its Old Welsh name Medcaut. The philologist Andrew Breeze, following up on a suggestion by Richard Coates, proposes that the name ultimately derives from Latin Medicata [Insula] (English: Healing [Island]), owing perhaps to the island's reputation for medicinal herbs.

This is typical speculation and the word 'perhaps' gives the game away!

The name Holy Island was in use by the 11th century when it appears in Latin as 'Insula Sacra'. The reference was to Saints Aidan and Cuthbert.

In the present day, Holy Island is the name of the civil parish and native inhabitants are known as Islanders. The Ordnance Survey, uses Holy Island for both the island and the village, with Lindisfarne listed either as an alternative name for the island or as a name of 'non-Roman antiquity'. "Locally the island is rarely referred to by its Anglo-Saxon name of Lindisfarne" (according to the local community website). More widely, the two names are used somewhat interchangeably. Lindisfarne is invariably used when referring to the pre-conquest monastic settlement, the priory ruins and the castle. The combined phrase The Holy Island of Lindisfarne has begun to be used more frequently in recent times, particularly when promoting the island as a tourist or pilgrim destination.

The monastery of Lindisfarne was allegedly founded around 634 by Irish monk Saint Aidan, who had been sent from Iona off the west coast of Scotland to Northumbria at the request of King Oswald. The priory was founded before the end of 634 and Aidan remained there until his death in 651. The priory remained the only seat of a bishopric in Northumbria for nearly thirty years. Finian (bishop 651–661) built a timber church "suitable for a bishop's seat". St Bede, however, was critical of the fact that the church was not built of stone but only of hewn oak thatched with reeds. A later bishop, Eadbert, removed the thatch and covered both walls and roof in lead.

Seriously? Now that's a massive amount of lead! Where did all of the oak come from? There aren't many trees on the island.

So, to recap:

1. The monastery was founded around 634. No details of size or construction materials are given.

2. It remained intact for thirty years.

3. Between 651 and 661, a timber church was built; but 634 plus 30 'intact years' is 664 - so which dates are correct? It's all just supposition and speculation.

4. Did Finian the bishop knock down and rebuild the original building?

5. St Cuthbert took over in 685 . He reformed the monks’ way of life to conform to the religious practices of Rome rather than Ireland. This caused bitterness, and he decided to retire and live as a hermit. He lived at first on an island (now called St Cuthbert’s Isle) just offshore, but later moved across the sea to the more remote island of Inner Farne.

6. St Bede was critical of the church because it was built of 'hewn oak' and not stone. In other words it was a wooden shack!

7. The wooden building had its thatched roof removed by Bishop Eadbert who succeeded Cuthbert, and proceeded to cover the roof and walls with lead. He was at Lindisfarne from 688 until his death in 698.

The ruins of a stone built church (priory) can be seen today and it was allegedly built sometime around 1150 and extended/modified over the succeeding years. It was abandoned around 1536.

Cuthbert allegedly died on 20 March 687 and was buried in a stone coffin inside the main church on Lindisfarne.

Remember that the church was a wooden shack covered in lead; not the stone remains seen today.

Eleven years later the monks opened his tomb. To their delight they discovered that Cuthbert’s body had not decayed, but was ‘incorrupt’ – a sure sign, they argued, of his purity and saintliness. His remains were elevated to a coffin-shrine at ground level, and this marked the beginnings of the cult of St Cuthbert, which was to alter the course of Lindisfarne’s history.

Miracles were soon reported at St Cuthbert’s shrine and Lindisfarne was quickly established as the major pilgrimage centre in Northumbria. As a result, the monastery grew in power and wealth, attracting grants of land from kings and nobles as well as gifts of money and precious objects.

The cult of St Cuthbert also consolidated the monastery’s reputation as a centre of Christian learning.

Sounds like a great money making scam!

The road into Lindisfarne was built around 1950 so getting to the 'centre of Christian learning', was not easy.

The church was made of wood and very basic, so it doesn't sound like a great tourist attraction!

Lindisfarne became the base for Christian evangelism in the North of England and also sent a successful mission to Mercia. Monks from the Irish community of Iona settled on the island.

Cuthbert's remains were later moved to Durham Cathedral (along with the relics of Saint Eadfrith of Lindisfarne). Eadbhert of Lindisfarne, the next bishop (and later saint), was buried in the place from which Cuthbert's body was exhumed earlier the same year, when the priory was abandoned in the late 9th century.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lindisfarne

Key Points:

1. Eleven years after Cuthbert's body was put into a stone coffin, the monks opened it up.

Why did they do that? Why wait eleven years?

2. It is alleged that the body had not decayed so this was taken a sign of his 'purity and saintliness'.

3. Much later, however, all that is moved from Lindisfarne are the remains of Cuthbert; so his body must have decayed and ceased to be 'incorruptible'!

That doesn't make sense and it sounds like the story is a lie.

The Cult of Cuthbert.

Cuthbert was born (perhaps into a noble family) in Dunbar, then in Anglo-Saxon Northumbria, and now in East Lothian, Scotland, in the mid-630s.

The simplicity of St Cuthbert’s shrine in Durham Cathedral today, belies its original appearance, which was ornate. It is said that just one of the many jewels decorating the shrine would have been worth a king’s ransom. The base of the shrine was made of expensive green marble and gilded. In the base were four seats, where pilgrims – especially the sick and lame – could kneel to receive the blessings of God and St Cuthbert.

Holy sleight of hand.

Cuthbert (allegedly) died on 20 March 687.

His body was taken back to the main monastery at Lindisfarne to be buried.

Eleven years later the coffin was dug up and re-opened, and his remains were found to be "incorrupt" or undecayed.

He was reburied in a new coffin, apparently over the original one, which is described in his biographies, and matches the surviving coffin closely.

This was placed above ground at the altar, and apparently covered with a linen cloth, an indication that Cuthbert was already regarded as a saint.

Why open up the 'holy relic' and why wait eleven years?

Why build another coffin that is used to house the original one?

Why not dispose of the old one?

The wood would have started to rot and decay after eleven years so it would make sense to get rid of it and honour the 'saint' with a new coffin.

This account is different from the previous one which states:

Cuthbert allegedly died on 20 March 687 and was buried in a stone coffin inside the main church on Lindisfarne.

Ten years later the monks opened his tomb. To their delight they discovered that Cuthbert’s body had not decayed, but was ‘incorrupt’ – a sure sign, they argued, of his purity and saintliness. His remains were elevated to a coffin-shrine at ground level, and this marked the beginnings of the cult of St Cuthbert, which was to alter the course of Lindisfarne’s history.

So, is it ten years or eleven?

Is it a stone coffin placed inside the church, or a wooden coffin buried in the ground?

The entire story looks like an attempt to produce a money making scam.

Tall stories.

In 875 the monks evacuated the abbey with the coffin, in anticipation of the Great Heathen Army (dreaded Vikings) moving into the area.

Really? How did they know that a Viking raid was imminent and that Lindisfarne would be targetted?

The safety of a bunch of bones and relics seems to have been more important than protecting the native people of the island!

Story 1.

The Viking raids and subsequent settlements define the period known as the Viking Age in Britain which had profound consequences on the development of the culture and language. The raids started in June of 793 CE when three ships docked at the shore by the abbey of Lindisfarne. The abbey's reeve, Beaduheard, believed he recognized them as those of Norse traders and, thinking they had lost their way, went out to direct them up the coast to the estate he thought they had been aiming for. Upon approaching the ships, however, he was instantly killed by the sailors who then sacked the abbey and murdered everyone they found inside or on the grounds; this was only the beginning.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1197/viking-raids-in-britain/

So, the abbey was sacked in 793! If this story is true, then the one about the monks fleeing in 875 carrying the 'holy relics' cannot be true as the monks wold have already been slaughtered and the relics totally wrecked.

Recall that the wooden coffin of the 'undecayed saint' was placed above ground at the altar; so it would have been easy to destroy it.

Story 2.

The Viking raid on the island of Lindisfarne, just off the Northumbrian coast, was not the first in England. A few years before, in 789, ‘three ships of northmen’ had landed on the coast of Wessex, and killed the king’s reeve who had been sent to bring the strangers to the West Saxon court.

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/lindisfarne-priory/History/viking-raid/

Notice the similarities of the two stories?

1. Three ships arrive at the coastline.

2. The reeve goes to meet the ships and is killed.

3. The crew of the three ships go on a destructive rampage and killing spree.

Interestingly, in story 1, the reeve Beaduheard, believed he recognized them as those of Norse traders and, thinking they had lost their way, went out to direct them up the coast to the estate he thought they had been aiming for. So Norse traders landing on English coastlines were a well know fact.

This means that the Norse 'Vikings' were friends with the English and not enemies.

Story 3.

Western Europe certainly bore the brunt of the Viking Invasion, perhaps no peoples more than those of the British Isles. The first Anglo-Saxon Chronicle reported that Norseman had made small raids in northern England beginning in 750. By 793, the raids had escalated and the Vikings attacked and burned the great Irish monastery at Lindisfarne, perhaps the first great ecclesiastical center of the British Isles.

Source: https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/viking-raids-ad-800-1150.

So, the Anglo - Saxon Chronicles state that the raids began in 750.

Which is the correct start date?

The date of the sacking and burning of Lindisfarne however, seems to be consistent at 793; which is very interesting and worth taking note of.

It is clear that trading with the friendly 'Northmen' was a common occurrence!

Wandering in the Wilderness.

Story 1.

For seven years the monks carried the coffin with them to various places in modern Scotland and Northumbria before settling it in the still existing St Cuthbert's church in Chester-le-Street until 995, when another Danish invasion led to its removal to Ripon.

The parish church of St Mary and St Cuthbert is a Church of England church in Chester-le-Street, County Durham, England. The church was established to house the body of Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, Bishop of Lindisfarne from 684 to 687.

They built a wooden church and shrine for St Cuthbert's relics, dedicating it to St Mary and St Cuthbert. Though there was no shortage of stone in the ruins of Concangis (the site of an old Roman fort) they did not build a stone church; it has been suggested they did not intend to stay for as long as they eventually did.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Mary_and_St_Cuthbert,_Chester-le-Street

Story 2.

It is thought that the community of St Cuthbert first settled across the river from Durham Peninsula, at the spot today occupied by St Oswald’s Church.

A carved Anglo-Saxon stone cross buried in the church walls seems to indicate that this was the case.

The White Church.

The first proper church constructed to house the body of Saint Cuthbert was the White Church or Alba Ecclesia, which was constructed of timber. It could have been a wattle and daub construction – named after the whitewash that would have covered its exterior.

It was probably conceived as a temporary structure as, in 998 (just three years after the community arrived), they consecrated a much larger church, the Ecclesia Major.

The Great Church (Ecclesia Major)

Consecrated in 998, this church was of stone. Uchtred, the earl of Northumbria, is reported to have used the local populace for its construction. This was not at all unusual – participating in the construction of a church was viewed as a pious act, and it was not difficult to enlist support.

Miracles performed at the shrine of St Cuthbert helped fuel people’s interest in the site, and quickly made Durham a place of great importance.

https://www.durhamworldheritagesite.com/learn/history/st-cuthbert/community

There are inconsistencies in the two stories.

In story 2, the wandering monks arrived in 995. They build a wooden church (Alba Ecclasia or White Church). Just three years later in 998, a stone church is consecrated (Ecclesia Major) .

Who paid for all of these building works?

Building two churches would take time and require plans, site surveys, enlistment of stone masons, labourers, carpenters, scaffolding, lifting cranes etc. They apparently had the aid of the earl of Northumbria and his monks who cleared the site.

In story 1, the wandering monks build St Cuthbert's church in Chester-le-Street and stay until until 995, when another Danish invasion makes them leave with the coffin and travel fifty miles to Ripon.

In story 2, the monks arrive in 995. In story 1, the monks leave in 995.

Key points:

1. The monks leave Lindisfarne in 875.

2. They wander for seven years.

3. They arrive in Chester Le - Street in either 882 or 883 depending on the source data.

4. Conflicting data states that they arrive in 995 and in 998 consecrate a stone church.

5. Further conflicting data states that the monks arrive at Chester - Le Street in 882 but leave for Ripon in 995 - before the church gets consecrated!

Why didn't the wandering monks go straight to Durham Cathedral? They would surely have been welcomed given the hype surrounding the saint and the alleged miracles that occurred.

It is clear that the stories are not based on any facts.

Wandering in the 'wilderness' of Scotland and Northumbria for several years carrying a 'holy relic'- mmmm, sounds like a familiar tale don't you think?

It was at Chester-le-Street that King Athelstan visited the coffin, and the textiles he gave were placed inside the coffin.

That's a very strange thing to do, put textiles inside the coffin. These are allegedly a stole that is worn around the neck and a piece of material that is draped over the left arm during the communion service. They could have been left outside the coffin; as were other gifts from the 'faithful'.

More stories.

Travelling once again, the cart with the coffin became stuck at Durham, which was taken as a sign that the saint wished to remain there.

It seems highly likely that a cart would get stuck a lot of times during the many years of wandering!

After repeated Viking raids, the monks fled from Lindisfarne in 875, carrying Saint Cuthbert's relics with them. The diocese of Lindisfarne remained itinerant until 882, when the monks resettled at Chester-le-Street, 60 miles south of Lindisfarne and 6 miles north of Durham. The see remained at Chester-le-Street until 995, when further Viking incursions once again caused the monks to move with their relics. According to the local legend of the Dun Cow and the Saint's hagiography, the monks followed two milk maids who were searching for a dun-coloured cow and found themselves on a peninsula formed by a loop in the River Wear. Thereupon Cuthbert's coffin became immovable, which was taken as a sign that the new shrine should be built on that spot, which became the City of Durham.

A more prosaic set of reasons for the selection of the peninsula is its highly defensible position, and that a community established there would enjoy the protection of the Earl of Northumbria, with whom the bishop at this time, Aldhun, had strong family connections. Today the street leading from The Bailey past the cathedral's eastern towers up to Palace Green is named Dun Cow Lane due to the miniature dun cows which used to graze in the pastures nearby.

Initially, a very simple temporary structure was built from local timber to house the relics of Saint Cuthbert. The shrine was then transferred to a sturdier, probably still wooden, building known as the White Church. This church was itself replaced three years later in 998 by a stone building also known as the White Church, which in 1018 was complete except for its tower. Durham soon became a site of pilgrimage, encouraged by the growing cult of Saint Cuthbert.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Durham_Cathedral

This account seems to indicate that the monks moved onto the peninsula which is where Durham Cathedral stands. The journey to Ripon isn't mentioned. The coffin is said to become immovable and so the spot at which is became stationary was to be the site of what is now Durham Cathedral.

Then the account gets really confusing as the simple wooden church and the subsequent wooden 'White Church' that was in other accounts said to be built in Chester Le - Street (outside the peninsula) , are now being built on the peninsula!

The body was moved within the cathedral at various points; perhaps in 1041, in 1069, to escape the Harrying of the North by William the Conqueror, in 1104 when the Norman cathedral was constructed, and in 1541 when the medieval shrine which was one of the principal English pilgrimage sites was destroyed during the Reformation.

The coffin was opened at various times during this period: a mid-11th century priest named Alfred Westou was in the habit of often combing the hair of the saint, and is also traditionally considered to have been responsible for placing the purloined (stolen) bones of Bede in the coffin.

Alfred Westou allegedly opened the coffin on numerous occasions, to wrap the saint's body in robes, and to trim his fingernails and cut or comb his hair and beard!

In 1827 the coffin was once again removed, having been found in a walled space at the site of the shrine.

The key words are: 'having been found'; which implies that the coffin was 'lost'!

By then there were up to four layers of coffin in fragmentary condition, taken to date from 1541, 1041, 698 and 687, housing a complete skeleton, and other human remains, though many of the contents had been removed earlier.

The key words are: 'housing a complete skeleton, and other human remains'.

The textiles (a stole and a maniple) were removed in 1827. The stole is worn around the neck and the maniple draped over the left arm. Cuthbert never used them.

The human remains were reburied in a new coffin under a plain inscribed slab, with the remains of the old coffins, which were removed in yet another opening of the burial in 1899.

So, the 'incorruptable' body seems to have been a lie as 'human remains' is what was reburied.

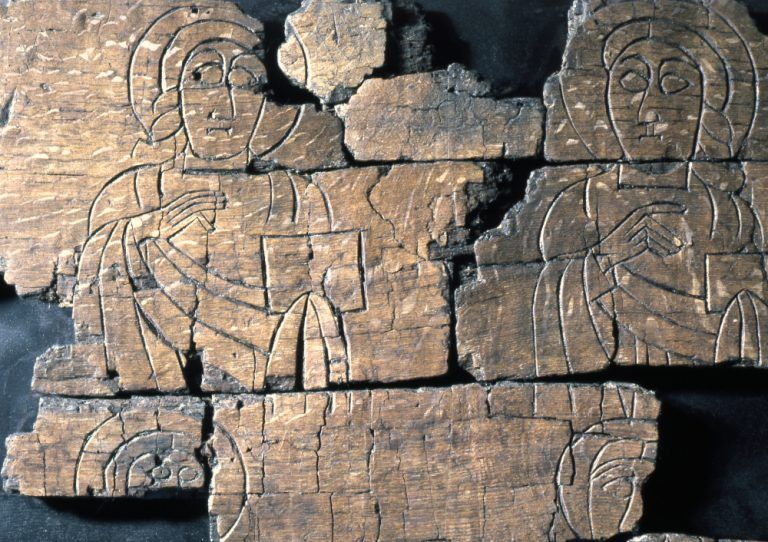

The wooden fragments totalled some 6,000, of which 169 showed signs of having been carved or engraved.

6000 wooden fragments, with 169 showing signs of engravings or carvings; that's a very small amount of engraving. So, the coffins were not intact! What about the contents - were they in pieces also?

The Jewish art-historian Ernst Kitzinger, then with the British Museum, made a reconstruction of the carved oak sections in 1939, which has subsequently been slightly re-arranged. The reconstructed coffin and most of the contents are on now view in the Cathedral Museum.

The fragments of St Cuthbert's coffin have been exhibited at Durham Cathedral since 2017.

Sources:

https://www.durhamworldheritagesite.com/learn/history/st-cuthbert/community

Puzzle pieces of St. Cuthbert's coffin.

The pieces of coffin, displayed in Durham Cathedral.

The coffin, made from English oak on Lindisfarne in 698 – 11 years after Cuthbert’s death – is regarded as the most important wooden object surviving in England from before the Norman conquest. Itt is engraved with the twelve apostles on one side (in two tiers), the archangels on the other side, and the Virgin and Child at one end, accompanied by inscriptions in both Roman and runic lettering.

In 1104, his coffin was opened again –some of the contents including the tiny gospel now in the British Library removed – and his remains moved to a grander shrine behind the altar of the new cathedral.

The shrine was destroyed in the dissolution, but unusually Cuthbert’s relics were left to be disturbed again in the 19th century when the wooden coffin was removed. His body was then described as just bones with some skin and ligaments attached.

So what happened to the 'incorrupt' body?

It was reburied for the last time, in an elaborate new coffin, in 1899. So why weren't the 6000 fragments of other coffins used to decorate this new one? They don't seem to have been considered important. Or were they not there at the time?

What is usually referred to as St Cuthbert's coffin is a fragmentary oak coffin in Durham Cathedral, pieced together in the 20th century, which between AD 698 and 1827 contained the remains of Saint Cuthbert, who died in 687.

Two apostles depicted on St Cuthbert’s coffin. These are very crude carvings and not done by a competent wood carver! There is no concrete evidence that the fragments are from a coffin used for Cuthbert - it's all speculation. The inscriptions are a mix of Runic and Latin letters, and this hides a great clue; but most miss the importance of this and the 'faithful' ignore it!

St. Cuthbert's Shrine at Durham Cathedral.

St Cuthbert's shrine tester designed by Sir Ninian Comper.

Sir John Ninian Comper (10 June 1864 – 22 December 1960) was a Scottish-born architect. He was one of the last Gothic Revival architects, his work almost entirely comprising restoration and embellishment of churches, ecclesiatical furnishings, stained glass and vestments. He is celebrated for his use of colour, iconography and emphasis on churches as a setting for liturgy. In his later works he developed the subtle integration of Classical and Gothic elements, an approach he described as 'Unity by Inclusion'.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ninian_Comper

https://www.durhamworldheritagesite.com/learn/architecture/cathedral/intro/cuthbert-shrine/keeper-of-the-shrine?fbclid=IwAR1W_uj-_PlJ7RgeD7tceMBuSdQ5Iqfea2VfneE4xtW5cm9tBFRnAPy1kwI

St. Cuthbert's shrine at Durham Cathedral. The tester can be seen hanging from the ceiling.

St Cuthbert's pectoral cross, one of the few items of value to have survived from the original shrine.

Meanderings and musings.

This is a close up of the robe as painted on the tester designed by Ninian Comper. It is made up of swastikas; one is a 'meander' the other is a stand alone swastika. Comper could have based his design on a Greek meander, but why have a highly contentious 'pagan' symbol (a swastika) on a 'Christian' image?

Pilgrims gather at the shrine yet don't seem to be bothered by the images of swastikas that adorn the robe!

Meanderings in other places.

This is a fallen section of carved masonry from Baalbeck in Lebanon. It is a meander in the style of a swastika; just like the so called 'Greek' meander. The term'Greco-Roman' is a misnomer that is used to hide a deeper truth.

The Gospels.

We are led to believe that the Norse Vikings invaded and went on destructive rampages on Lindisfarne and on the mainland; yet, the artwork of the Gospels is totally Norse! The intricate designs and representations of animals is definitely not 'Christian'! The repeated use of 'Odin's Horn' or Triskelion is blatantly obvious. Why use the artwork of the hated 'pagan' Vikings who raided, plundered and massacred to illustrate a 'Christian' book? It makes no sense!

The gospels according to speculation.

At some point in the early 8th century the illuminated manuscript known as the Lindisfarne Gospels, an illustrated Latin copy of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke and John, was made, probably at Lindisfarne. The artist was possibly Eadfrith, who later became Bishop of Lindisfarne.

The Lindisfarne Gospels manuscript was produced in a scriptorium in the monastery of Lindisfarne. It took approximately 10 years to create.

It is also speculated that a team of illuminators and calligraphers (monks of Lindisfarne Priory) worked on the text, but if so, their identities are unknown. Some time in the second half of the 10th century, a monk named Aldred added an Anglo Saxon (Old English) gloss to the Latin text, producing the earliest surviving Old English copies of the Gospels. Aldred attributed the original to Eadfrith (bishop 698–721). The Gospels were written with a good hand, but it is the illustrations, done in an insular style containing a fusion of Celtic, Germanic and Roman elements, that are considered to be of the most value. According to Aldred, Eadfrith's successor Æthelwald was responsible for pressing and binding the book, before it was covered with a fine metal case made by a hermit known as Billfrith. The Lindisfarne Gospels now reside in the British Library in London, a location which has caused some controversy amongst some Northumbrians. In 1971, professor Suzanne Kaufman of Rockford, Illinois, presented a facsimile copy of the Gospels to the clergy of the island.

So, let us consider the available information:

1. The 'illustrated Latin copy' was 'probably' made at Lindisfarne.

2. The artist was 'possibly' Eadfrith - the bishop of Lindisfarne. Amazingly, he made 90 of his own colours with only six local minerals and vegetable extracts. It took approximately 10 years to create. Its pages are vellum, and evidence from the manuscript reveals that the vellum was made using roughly 150 calf skins. The book is 516 pages long. The text is written "in a dense, dark brown ink, often almost black, which contains particles of carbon from soot or lamp black". The pens used for the manuscript could have been cut from either quills or reeds, and there is also evidence to suggest that the trace marks (seen under oblique light) were made by an early equivalent of a modern pencil.

The earliest manufacturing of pencils is said to be around 1600 so this 'early equivalent' sounds far - fetched; or the manuscript is a more modern forgery!

There is a huge range of individual pigments used in the manuscript. The colours are derived from animal, vegetable and mineral sources. Gold is used in only a couple of small details. While some colours were obtained from local sources, others were imported from the Mediterranean. The blue was long thought to be ultramarine from Afghanistan, but analysis with Raman microscopy in the 2000's revealed it to be indigo. The medium used to bind the colours was primarily egg white, with fish glue perhaps used in a few places. Janet Backhouse emphasizes that "all Eadfrith's colours are applied with great skill and accuracy, but ... we have no means of knowing exactly what implements he used".

3. Professor Michelle Brown added that Eadfrith "knew about lapis lazuli (a semi-precious stone with a blue tint) from the Himalayas but could not get hold of it, so made his own".

Really? How on earth did she work that out?

4. It might be that a team of unknown illustrators worked on illustrating the book! Well, in that case they would all have to be highly trained calligraphers!

5. Some time in the second half of the 10th century, a monk named Aldred produced copies of the Gospels and transcribed them from Latin into Old English.

The Gospels were written with a good hand, but it is the illustrations, done in an insular style containing a fusion of Celtic, Germanic and Roman elements, that are considered to be of the most value.

There is no 'fusion', the illustrations are pure Norse in their design!

6. Eadfrith's successor pressed and bound the book.

7. A hermit named Billfrith made a metal case for the book.

8. The book is unfinished - so why bind an unfinished book and make a jewelled metal case for it? It doesn't make sense.

KEY POINTS:

The Gospels were produced when the church/priory was allegedly a wooden building that had a lead roof and walls covered in lead. The stone building that lies in ruins today was built over 400 years later. Life on Lindisfarne was often harsh and the conditions inside a lead covered wooden building would be pretty basic. The day to day chores and religious rituals would not leave a lot of time to spend on producing a highly ornate and well executed book. The materials would be very expensive to buy, so where did the money come from? Lindisfarne is cut off from the mainland when the tide is in and there are areas of quicksand to trap the unwary who decide to walk across the sands when the tide is out. The causeway was constructed in the mid-1950's. Until then, the Pilgrims Way footpath, marked with a line of upright poles, was the only access to the island; unless you used a boat.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lindisfarne

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lindisfarne_Gospels

Blame the Vikings.

The etymology of "Viking" is uncertain. The word Viking was introduced into Modern English during the 18th-century Viking revival, at which point it acquired romanticised heroic overtones of "barbarian warrior" or noble savage.

In 793, a Viking raid on Lindisfarne caused much consternation throughout the Christian west, and is now often taken as the beginning of the Viking Age. There had been some other Viking raids, but according to English Heritage this one was particularly significant, because "it attacked the sacred heart of the Northumbrian kingdom, desecrating 'the very place where the Christian religion began in our nation'". The D and E versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle record:

("In this year fierce, foreboding omens came over the land of the Northumbrians, and the wretched people shook; there were excessive whirlwinds, lightning, and fiery dragons were seen flying in the sky. These signs were followed by great famine, and a little after those, that same year on 6th ides of January, the ravaging of wretched heathen men destroyed God's church at Lindisfarne.")

Key points:

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of Alfred the Great (r. 871–899). Multiple copies were made of that one original and then distributed to monasteries across England, where they were independently updated. In one case, the Chronicle was still being actively updated in 1154.

Nine manuscripts survive in whole or in part, though not all are of equal historical value and none of them is the original version. The oldest seems to have been started towards the end of Alfred's reign, while the most recent was written at Peterborough Abbey after a fire at that monastery in 1116. Almost all of the material in the Chronicle is in the form of annals, by year; the earliest are dated at 60 BC (the annals' date for Caesar's invasions of Britain), and historical material follows up to the year in which the chronicle was written, at which point contemporary records begin. These manuscripts collectively are known as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.

The Chronicle is biased in places. There are occasions when comparison with other medieval sources makes it clear that the scribes who wrote it omitted events or told one-sided versions of stories. There are also places where the different versions contradict each other.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglo-Saxon_Chronicle

The Anglo - Saxon Chronicle.

All of the surviving manuscripts are copies, so it is not known for certain where or when the first version of the Chronicle was composed.

Key Point:

All of the surviving manuscripts are copies, so it is not known for certain where or when the first version of the Chronicle was composed, or if the surviving versions are based on truth.

As with any historical source, the Chronicle has to be treated with some caution. For example, between 514 and 544 the Chronicle makes reference to Wihtgar, who is supposedly buried on the Isle of Wight at "Wihtgar's stronghold" (which is "Wihtgaræsbyrg" in the original) and purportedly gave his name to the island. However, the name of the "Isle of Wight" derives from the Latin "Vectis", not from Wihtgar. The actual name of the fortress was probably "Wihtwarabyrg", "the stronghold of the inhabitants of Wight", and either the chronicler or an earlier source misinterpreted this as referring to Wihtgar.

The dating of the events recorded also requires care. In addition to dates that are simply inaccurate, scribes occasionally made mistakes that caused further errors. For example, in the [D] manuscript, the scribe omits the year 1044 from the list on the left hand side. The annals copied down are therefore incorrect from 1045 to 1052, which has two entries. A more difficult problem is the question of the date at which a new year began, since the modern custom of starting the year on 1 January was not universal at that time. The entry for 1091 in [E] begins at Christmas and continues throughout the year; it is clear that this entry follows the old custom of starting the year at Christmas. Some other entries appear to begin the year on 25 March, such as the year 1044 in the [C] manuscript, which ends with Edward the Confessor's marriage on 23 January, while the entry for 22 April is recorded under 1045. There are also years which appear to start in September.

The manuscripts were produced in different places, and each manuscript reflects the biases of its scribes. It has been argued that the Chronicle should be regarded as propaganda, produced by Alfred's court and written with the intent of glorifying Alfred and creating loyalty.[39] This is not universally accepted,[notes 4] but the origins of the manuscripts clearly colour both the description of interactions between Wessex and other kingdoms, and the descriptions of the Vikings' depredations. An example can be seen in the entry for 829, which describes Egbert's invasion of Northumbria. According to the Chronicle, after Egbert conquered Mercia and Essex, he became a "bretwalda", implying overlordship of all of England. Then when he marched into Northumbria, the Northumbrians offered him "submission and peace". The Northumbrian chronicles incorporated into Roger of Wendover's 13th-century history give a different picture: "When Egbert had obtained all the southern kingdoms, he led a large army into Northumbria, and laid waste that province with severe pillaging, and made King Eanred pay tribute."

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglo-Saxon_Chronicle

G. O Sayles, in his book The Medieval Foundations of England has this to say in Chapter 1 - The Sources of History before 871:

"It should be said at once that the evidence on which we must rely for our knowledge of what was happening between the fifth and the ninth centuries is, with few exceptions, fragmentary and equivocal and presents an easy target for destructive criticism. This is particularly true of the period after 400, once termed the 'two lost centuries' of British history, when our sources are so scanty that we cannot reconstruct with confidence even a rough chronology of developments. And since so often we have doubtful information about still more doubtful events, it is inevitable that speculation and even invention should find free reign. Furthermore, when we do have facts at our disposal, what is most disturbing is the numerous occasions when one type of evidence seems to come into direct conflict with another."

Source: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=s0ufDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT23&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=3#v=onepage&q&f=false

So this is the key point: there are no certainties, just speculation and invention!

Alcuin the unknown!

Alcuin was born in Northumbria, presumably sometime in the 730s. Virtually nothing is known of his parents, family background, or origin.

Alcuin of York (/ˈælkwɪn/; Latin: Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus; c. 735 – 19 May 804) – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was an English scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student of Archbishop Ecgbert at York. At the invitation of Charlemagne, he became a leading scholar and teacher at the Carolingian court, where he remained a figure in the 780s and 790s. "The most learned man anywhere to be found", according to Einhard's Life of Charlemagne (c. 817–833), he is considered among the most important intellectual architects of the Carolingian Renaissance. Among his pupils were many of the dominant intellectuals of the Carolingian era.

During this period, he perfected Carolingian minuscule, an easily read manuscript hand using a mixture of upper- and lower-case letters. Latin paleography in the eighth century leaves little room for a single origin of the script, and sources contradict his importance as no proof has been found of his direct involvement in the creation of the script. Carolingian minuscule was already in use before Alcuin arrived in Francia. Most likely he was responsible for copying and preserving the script while at the same time restoring the purity of the form.

He allegedly wrote many theological and dogmatic treatises, as well as a few grammatical works and a number of poems. In 796, he was made abbot of Marmoutier Abbey, in Tours, where he remained until his death.

With regard to the events in Lindisfarne, he wrote the following:

"Never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race ... The heathens poured out the blood of saints around the altar, and trampled on the bodies of saints in the temple of God, like dung in the streets."

Key Points:

1. Alcuin was born in Northumbria, presumably sometime in the 730s. Virtually nothing is known of his parents, family background, or origin.

2. This is a presumption and sounds like a total fabrication that has been back-projected in order to promulgate a false history and hide the truth.

3. Apart from the descriptions in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, there is no other historical mention of “immense whirlwinds and flashes of lightning, and fiery dragons” in Northumbria.

Celtic.

“The term ‘Celtic’ is a magic bag into which anything may be put, and out of which almost anything may come … Anything is possible in the fabulous Celtic twilight, which is not so much a twilight of the gods as of reason.”

J.R.R. Tolkein.